Artificial intelligence promises to augment our collective processing capacity. But on an individual level it is a neurotoxin that promises learners only artificial ignorance.

We are all familiar with the fact that unused muscles weaken, then atrophy. If one were to permit a developmentally normal, able-bodied child to rely on mobility scooter for transport they would, over time, develop physical incapacity where none had existed: an induced disability.

Thus, it shouldn’t be difficult to grasp that permitting children to rely on artificial intelligence ‘assistance’ such as ChatGPT will weaken, then atrophy, their intellectual capacity: an induced disability.

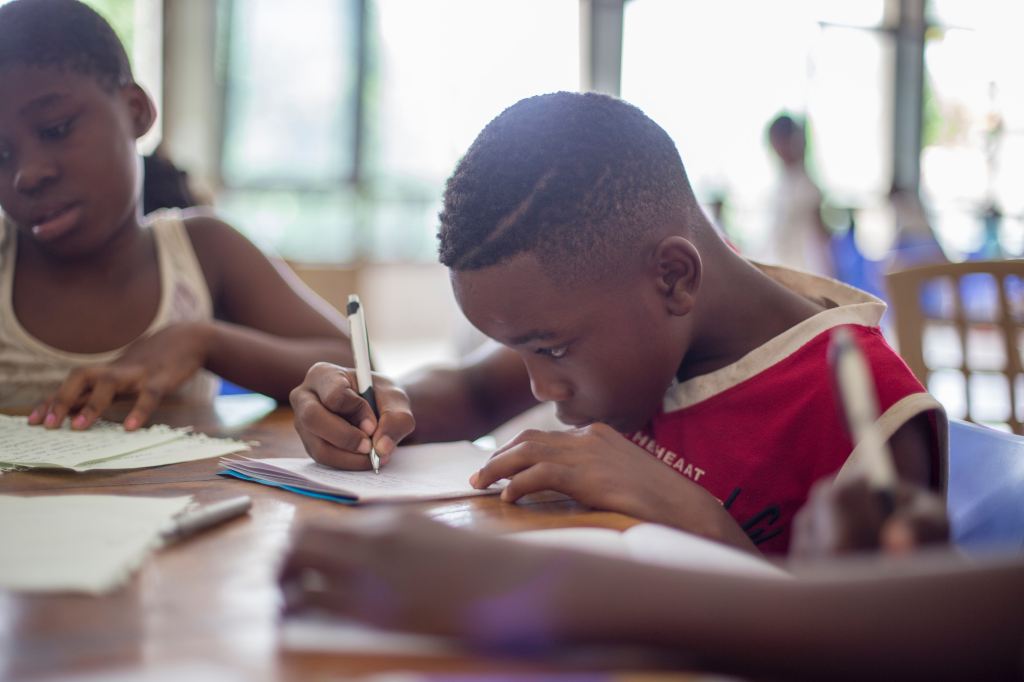

Writing a better brain

Writing is not just the product of thought. It has a unique ability to generate thought.

- ‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking’ ~Joan Didion, journalist.

- ‘With each of the new [ancient] writing systems, with their different and increasingly sophisticated demands, the brain’s circuitry rearranged itself, causing our repertoire of intellectual capacities to grow and change in great, wonderful leaps of thought.‘ ~Maryanne Wolf, Director of the UCLA Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice.

As Wolf explains in her 2007 book Proust and the Squid (from which the above quote is taken) there is neither gene nor discrete neurological structure that enables humans to read and write. Literacy relies on complex, non-axiomatic collaborations between a variety of perceptual and cognitive systems.

Put another way: preliterate and literate brains are structured the same. What changed human history was not a novel biological development but the recruitment of extant neurological capabilities to perform a novel task.

Does that bend your mind a little?

It should.

Writing is not just a means of expression, like speech. It is a process and practice that improves cognitive function; it rewires the brain.

Put another way: it isn’t that smart people are better writers, it’s that writing makes people smarter.

All of us who care about children’s long-term well-being, whether they are our students or offspring, should be anxious to help them develop their fullest intellectual capacity.

We are on a hot rock spinning towards oblivion. Life for kids who are in today’s classrooms will be complex beyond the wildest imaginings of us scions of the analogue order. The will need to be wily, resilient and resourceful AF.

Being laissez-faire about kids substituting artificial intelligence for study makes as much sense as being laissez-faire about children playing with live hand grenades: cool, if you don’t mind the maiming.

There are three key reasons I won’t use generative AI and emphatically discourage its use by students.

Neural stunting

A well-used brain grows, according to Pauwels et al. (2018):

“Practice leads to improvement in and refinement of performance… and this dynamic behavioral process is associated with altered brain activity…. Besides functional brain changes, practice also induces structural changes, such as alterations in regional brain grey and white matter structures.”

A brain that does not practice complex skills fails to grow, just as the disused muscle slumbers undeveloped. The brain becomes stunted compared to what it could have been, could be, with training.

A less-developed brain with fewer neural connections and reduced processing efficiency does not just affect reading or writing skills. If affects a person’s ability to learn, communicate and adapt.

Every time a student outsources their thinking to AI, they are sabotaging their long-term mental flexibility.

Educators and parents bear responsibility for this, insofar as we perpetuate a results-based learning environment. When we prioritize the ‘right answer’, kids get the message that process doesn’t matter. It makes sense for them to use any means necessary to get the answer that gets the desired grade.

We grown-ups need to rewire our thinking and explicitly focus on the learning process. This is not going to be easy, given the baggage of 150-odd years of rote education, but we have to begin. This might be as simple as grading the steps of an essay instead of the final draft, or doing away with grades altogether in favor of a feedback system. (For more ideas: Ungrading with Anthony Lince)

Concentration of intellectual capital

Late-capitalism has succeeded in concentrating financial capital into the hands of a vanishingly small number of individuals. The grotesqueries of this are felt every time an ordinary US citizen needs insulin or an EpiPen, or wants to go to college. There are felt a thousandfold-moreso by the 650 million people living in extreme poverty around the globe.

This concentration accelerated wildly during the Covid-19 pandemic: ‘Billionaires’ wealth has risen more in the first 24 months of COVID-19 than in 23 years combined,’ Oxfam reported. ‘The total wealth of the world’s billionaires is now equivalent to 13.9 percent of global GDP.’

Put another way: those of us not born to oligarchy face ever-slimmer chances of rising to the top. Financially, anyway.

Until now, those not to the manor born could at least, to paraphrase Britpop’s finest cynic, Jarvis Cocker, use the one thing we’ve got more of: our minds.

Unless we allow kids to consign their thinking skills to artificial intelligence.

To be clear, I don’t believe there is a conspiracy among Musk, Zuckerberg, et al. to make the rest of the population dumber so they can rule in full-blown, unchecked Bond-villainesque splendor (mwah haha).

But there is a real danger of that dystopia becoming a reality through lack of vigilance on the part of educators, parents and politicians.

Big tech does not care about us. Does not exist to serve us. Is not our toy.

In the same way wealth-accumulation takes on a life of its own, with money begetting money, intellectual capital accretes to the intellectually adept. Students who read, write and think critically enhance the neural circuits for these skills, gaining efficiency, automaticity and self-confidence.

This enables them to tackle bigger challenges, be more creative, rise to the top. The better they get at learning, the more dauntless they will be; the more quickly they will evolve to meet new demands.

Students who let AI think for them will cultivate artificial ignorance, sap their innate learning abilities and dull themselves into ever-shrinking spirals of incompetence and self-doubt.

They will be victims, not victors, in the knowledge economy.

Diminishing returns

Generative AI is trained on scads of data.

Perhaps one of the reasons it shines is that current tools were trained on the laborious output of human brains. Right now, the machine is well-nourished.

Like any other extractive technology, AI’s potential is limited by the quantity of quality raw material available. As AI is increasingly used to generate blog posts, articles, images, etc., it will, perforce, eat itself. Like a hideous, post-post-modern game of telephone, machine learning will digest its own output to spew forth content that is increasingly bland, distorted and derivative: a garbled self-parody that will further diminish culture and conversation.

This is not an abstract concern. There are AI tools I recommend to students on a limited basis, such as Grammarly, for English-learners or novice writers who need grammatical training wheels. I discourage competent writers from using it because it flattens good writing.

Neither it, nor any AI tool, can distinguish a truly beautiful sentence nor appreciate the work of (to borrow from Salinger) an experienced literary stunt-pilot. Creative word usage, neologisms, daring sentence structures all fall foul; the machine brain cannot cope with linguistic audacity.

This is the chief weakness and biggest threat of artificial intelligence: it prefers the commonplace to the extraordinary and the predictable to the audacious.

Our world needs bold solutions and novel ideas, which it will not get from a conservative technology.

There are plenty of things to outsource to AI: reviewing medical data, tracking undersea tremors, preventing fraud. But not education.

The children whom we want to see thrive need every iota of intellectual capacity and creativity that dedicated teaching and rigorous practice can bestow. Otherwise, we doom them to artificial ignorance.

What are your views on AI in the classroom? Share in the comments?