Welcome to ‘Between the Lines’ – interviews with teachers, writers and writing teachers on specific aspects of their craft.

Light filters into Michael Downs‘ basement office, as if it were underwater.

Twin decorative dragonflies, backlit on a windowsill, and a red goose-neck lamp stretched into a honk, heighten the effect of a numinous natural space. It is, he says, the best writing room he’s ever had.

And he’s had a few to compare.

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Downs rode economic currents with his family, first to Vermont then Arizona. After graduating from college, his journalism career took him back to Hartford for a spell; he met a woman and fell in love, moved with her to Montana; later, they moved to Arkansas, where he attended grad school, then to Baltimore in pursuit of work.

Downs nods in recognition at the mention of the 1960s-70s cadre of hard-drinking, fly-fishing Montana writers: ‘Tom McGuane, those guys, sure.’ Though a former sportswriter, Downs doesn’t need to prop his ego with tales of a trout [this] big.

His body of work reveals someone who lets nuance speak for itself; someone who illuminates and distils the details, then leaves them to do the work.

Downs’ published books include narrative non-fiction (the River Teeth Literary Prize-winning House of Good Hope: A Promise for a Broken City); a historical-short story collection, The Greatest Show, about the 1944 Hartford Circus Fire; and The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist, a novel.

As befits his journalism background Downs, now a professor of English literature and director of the Master’s Program in Professional Writing at Towson University, regularly publishes short stories, essays and reportage. As befits a scribe, he also turns his hand to ghostwriting and editing.

Gathering words

The TV Guide, cereal boxes, the Bible, historical romance novels, Of Mice and Men, comics: ‘I read everything,’ Downs said. ‘I loved words; wanted to understand them.’

His precocious reading meant he struggled to keep pace with their sounds. ‘I’ve learned so many words just by reading that my pronunciation, throughout my life, has been terrible. “Inchoate” — is that in-ko-ate or in-cho-ate? I can never remember, but I know what it means.’

There is something to be gleaned from this primary engagement with writing as text. Technology has gifted the writer, or would-be, many ways to engage and construct, but there is power in being able to seed words on a page and watch the lines grow into a riotous harvest

Downs relishes the labor of it, the physicality of writing (more on that in a moment). His most influential teachers were the ones who, ‘demanded more of me than I thought I could do. And did so unapologetically. That helped me understand my capacities.’

The purpose of literature

Exploring his capacities took Downs to the University of Arkansas MFA program in the late 1990s. This was his grounding in Shakespeare, the King James Bible, Don Quixote, and teaching. ‘I wanted my tuition paid,’ he says with a grin. ‘But it was a wonderful thing for a variety of reasons.’

Foremost, teaching (as any teacher who gives a damn will tell you) demands the kind of close study many students elude. ‘I had to break down stories, novels, sentences; I had to do the craft aspect better than I would have otherwise.’

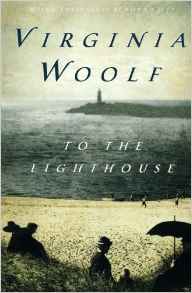

The process of deconstruction facilitates a deeper understanding of construction; clever writer/teachers seize opportunities to teach authors they love, or genres they want to better understand. Downs, for example, taught a historical fiction course while writing a historical novel.

Teaching writing is about more than just craft, though; Downs increasingly focuses on a less-discussed aspect of literature:

This generation has had a lot to deal with. It’s clear in their stress, their anxiety, what they talk about. What I want to do is use literary work – either the writing of it or the reading of it – to help them understand that the world is worth it, that it’s beautiful, that the unexpected doesn’t have to be dread inducing. The unexpected can also be the reason you get up in the morning. I spend more time now talking about beauty and how to use literature to help yourself get along in the world.

For all the joy he’s found in 30-odd years of education, Downs is transitioning to full-time writing. ‘I’m rich in former students, but I’m not as rich as I’d like to be in books.’

During his recent Fulbright Scholar year in Krakow, he encountered a quote by the Polish poet Adam Zagajewski stencilled on a staircase: ‘it is not time that is lacking, only focus’.

‘Like so many other writers, especially writers who teach, I say things like ‘I don’t have a lot of time, I’m trying to find the time to write, etc.’ he says. ‘I read that quote and thought, ‘I need to change my focus.’ My focus has been students, for decades. I’ve been grateful for teaching at a university and having the summer to write, but I’m old, I’m a slow writer, and I want more.’

Part of how Downs accesses ‘more’ is through what he playfully refers to as ‘method writing’. He was kind enough to share examples and insights on this element of craft.

On Method Writing

Q: Why is it important for writers to get out from behind the desk and get their hands dirty?

A: Emily Dickinson didn’t do that, and she pulled off some good stuff. So I don’t want to say it’s a moral imperative, but for some writers, young writers especially, it’s important to get out of your own belly button. There is a world out there, experiences, things that are tactile, not just in your head. We take in experience through our five senses, then meditate on them. If you don’t have experiences, you don’t have stories. You can have think pieces, but you don’t have stories.

Q: What is your first memory of tangible experience that led to, or was integral to, a piece of writing?

A: When I was an 8th grader, I had a paper route. A stray dog used to follow me. I’d stop at a convenience store, buy some food, share it with the dog. It followed me for weeks, until it followed me across a road one morning, as the sun was rising over the mountain. Someone came along, driving fast into the sun, and hit the dog. And it fell to me to pull the dog off to the side of the road – still breathing, but clearly dying, and to stay with the dog.

Some time later, I went to a writing camp for kids, and a college professor told us to explore stories by writing about the parts of our lives that confused us. And I went back to that moment. It was a successful story, because I remembered the weight of the dog, what it felt like to touch it; that it was still breathing. That was the first time physical experience worked itself into my writing.

Q: How does tactile experience operate as a research mode in fiction versus non-fiction?

A: When I’m doing narrative non-fiction, I’m experiencing the world as me, so paying attention to my five senses. When I’m doing it in fiction, I’m trying to be someone else. So if they have experiences that I haven’t, I have figure out how to get close to those experiences. I try to save my imagination from doing too much work, or from getting it wrong. The imagination isn’t always right.

When I was writing about a woman who was burned in the Hartford circus fire, I drew from this wonderful Red Cross pamphlet about how people were treated after that fire, because it was groundbreaking. But also – I‘m going to sound a little crazy now – I needed to know what it felt like to be burned. I put my hand over the gas ring [on my stove], and held it as close as I could, for as long as I could. I did not hurt myself, but I got an idea of the feeling of a sustained burn. And that’s what I wrote.

If I hadn’t held my hand over that fire, I could not have imagined how it felt. It was cold.

Q: How do you incorporate method writing into second or third person POV?

A: It’s about coming to a place of focus where I can combine my engagement with the world and my imagination to say. If it’s working, it becomes transcendent. The words end up there; I don’t know exactly what brought them, but they are right, and I could never find those same words again.

Q: How do you know when to stop experiencing and start writing?

A: It’s always time to sit down and start writing.

It’s time to start experiencing when – in fiction – I don’t know what the character is experiencing. The character is in a situation and it’s time to figure it out. When working on the Horace Wells novel, I was struggling with the fact the main character wasn’t an enjoyable person to be around. He wasn’t super successful, he was whiny, he wasn’t that bright. I had to figure out a way to make him palatable.

How it happened surprised me. I went to a museum that had his tools, his notebooks, his death mask. They brought out the death mask. I put on white gloves and picked it up. His face was small, surprisingly small. I started touching his face. And I decided that his wife had touched his face. That though he betrayed her, and made her life difficult, she loved him. And if she loved him, I could love him through her. That changed him as a character, from a nebbish to a person who was loved by his wife.

Q: What is a rookie mistake writers make when attempting this?

A: To think their experience is how the character would have experienced it. John Keats said that Shakespeare possessed this amazing quality of self-nullification; he could stop being Shakespeare and be someone else. That’s how so many [of his] characters are who they are.

I encourage students to work at not being themselves. As a writer, your job is not to ask, what would I be doing if I were them? You have to become that character and know. Andre Dubus talks about studying Zen and becoming the word as he writes. It has to do with focus.

Q: Which writers do this particularly well?

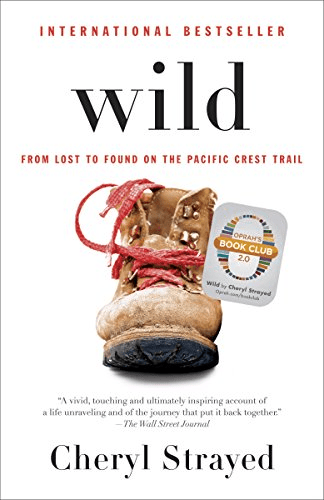

A: Andre Dubus, absolutely. He was a man who wanted to be out there in the world, make stuff, experience stuff. Alice Munro, you know she’s out tromping the fields. Louise Erdrich, a favorite of mine, she doesn’t just sit behind a desk. Joan Didion, of course.

Q: What is an assignment or exercise you use to teach this to your students?

A: A terrible thing happened near my campus more than 100 years ago, before campus was there. A black teenager was lynched. I wanted the students to write about it. We walked to the site and sat for an hour; looked at the trees and the jail, which is still there, and touched the walls, looked at the sun. I wanted them to imagine how it was then, and see how it is now.

Downs Recommends

The piece of writing that changed your life before age 18?

The Lord of the Flies. It completely freaked me out. I hadn’t know that boys could be so cruel. I was a shy, awkward boy who wore glasses. I could have been Piggy.

The piece of writing that changed your life as an adult?

William Kennedy’s Ironweed, a profound and magical novel. Kennedy – a former journalist who never stopped thinking of himself as a journalist – wrote a novel set in a small north-east city, Albany, NY, that nobody paid much attention to. I wanted to write about Connecticut, about a small town no one paid much attention to, and this [novel] gave me the blessing.

A classic you love to teach?

‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’ by Flannery O’Connor and ‘Sonny’s Blues’ by James Baldwin. If I could only teach two stories for the rest of my life, it would be these two.

I love what Baldwin writes about art in that last scene; he’s writing about music, and Sonny’s blues, but … I’ll blow the quote, they were doing it at the risk of their own lives, but they had to do it, because we need those stories, and we need to make them new. It’s a gorgeous description of why we need stories.

‘Good Man’ because it is such an inexplicable story. Students have no idea what’s coming. Their mouths drop open. It’s a perfect story for proving to them that you can’t say what a story means.

A work you love to teach from 21st century?

Lydia Davis Varieties of Disturbance – she blows up the idea of what a story is, disregards everything anybody says. There’s a novella in it, which purports to be a sociological studies about get well cards written by a second grade class; it is just heartbreaking, funny, and reveals so much. She also has one-sentence stories in the book. Literally one sentence.

A book about writing every writing student should read?

Colum McCann’s Letters to a Young Writer.

A book + film adaptation combo you love?

The Good Lord Bird by James McBride, which was turned into a TV series with Ethan Hawke.

A living writer you’d love to hang out with?

Olga Tokarczuk. I’m fascinated by the concept she discusses in her Nobel Prize speech of the ‘tender narrator’ – a new approach to narrating fiction. A different point of view.

Your perfect writing space?

If space and time are related, it’s more about the time than geography. If I create the time, the place doesn’t matter. I can be on a park bench, a balcony, a windowless room, sitting in the front seat of my car.

What are you working on now?

I’ve written about six essays and would like to write another four to six and put together a collection. I have some ideas that have been – there is no other way to say it – that have been strong in me lately. They are wanting to come out.

Connect

- Web: Michael-Downs.net

- Goodreads: Michael Downs