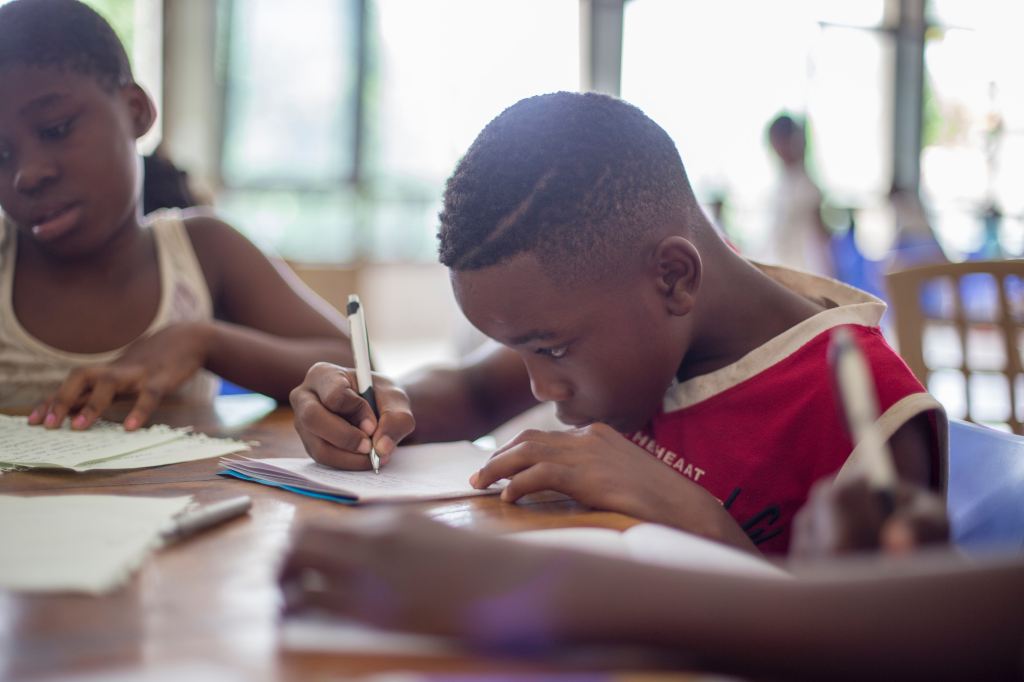

Grab a pen and paper and hone your word skills through play!

Native English speakers only need to learn around 9,000 words to read proficiently (Nation, 2014; Qian & Lin, 2019). This, out of a lexis of over 170,00 words (and growing!)

Hence most of us walk, eat and talk on a daily basis rather than shuffle, feast or murmur.

We’re creatures of habit. The words we use frequently become top-of-mind, and therefore likely to be used again. Our routine vocabulary shrinks like a puddle in the sun.

One way to prevent, indeed, reverse, this trend is to play with words.

Reading, crossword puzzling, etc., can build our word banks but having a fine working vocabulary means being able to summon novel words and express ourselves in new ways. Like play piano, or basketball, this skill requires practice.

The following drills are designed to be pen-and-paper; no reference to outside sources required. Use the back of an envelope, a napkin, scribble on your hand like a teenager, draw in sand on the shoreline.

The goal is to tap your linguistic aquafer. If you feel inspired to augment your vocabulary through reading or dictionary browsing, all to the good, but no pressure.

Grab your quill and parchment and let’s away.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Pre-root-ixes: Prefixes, root words and suffixes

Straightforward: choose a prefix, root word or suffix and list as many words containing it as you can.

- Prefix suggestions: ex, dis, im, dis, pre, un

- Root suggestions: auto, corp, derm, lum, tele

- Suffix suggestions: ism, ity, ment, ness, tion/sion

Word transformation

This is a game I designed to improve upper-level ESL students awareness of parts of speech (POS) and the flexibility of English vocabulary. It’s simple, take a noun or verb, then come up with all the permutations of it you can, including words that contain it, collocations or sayings.

It works best when you think systematically about POS. Let’s use like as an example.

- Verbs: to like, to dislike

- Nouns: like, likelihood, liking, dislike

- Adjectives: like, likeable, likely

- Adverbs: like, likely, unlikely

- Preposition: like

- Conjunction: like

- Collocations/sayings: eat like a horse, go over like a lead balloon, off like a shot, like water off a ducks back, look like a million dollars, etc.

CAS – colloquialisms, aphorisms and sayings

Here, the goal is to list informal language terms that either

- contain a particular word (as in the example above)

- relate to a particular subject (e.g., work, money, travel)

Take ‘time’ as an example. The first category might include

- time and tide way for no man

- a stitch in time saves nine

- once upon a time

- time is (not) on their side

- time out of mind

The second

- to take a rain check

- down to the wire

- from here to eternity

- jump the gun

- Rome wasn’t built in a day

Single-word prompts

This drill was the result of being bored of my journal. Left to itself, my squirrelly brain chews over the same topics like its storing fat for winter. So I wrote a random word at the top of each page then, each day, wrote something inspired by it.

Try this for five, seven, 10, 14 days. See what fun your mind has.

Alphabets

Another fast, fun list drill. Jot the alphabet vertically on a sheet of paper then fill it in with words from a given category: adverbs, cities, animals, desserts, compound nouns.

Warm up with a big category like plants or household objects then get esoteric: can you complete the alphabet with shades of blue, pre-20th century literary heroines or 80s song titles?

What do you see?

Prior to writing my novel Ibiza Noir, I wrote 700 words of pure description a day for 30 days. No attempt at narrative, simply drew the most vivid word-pictures possible.

- Set a time or word-count goal, e.g., write for 10 minutes without stopping, or write 500 words.

- Choose an object of reasonable complexity, a flower, or your living room, and describe it in as much detail as you can muster. Imagine you are describing it to an artist; you want their rendering to be as close to reality as possible.

- Challenge yourself to apply this descriptive writing practice to real-world scenes. Go sit in the park, or on a bench at the mall, and write your allotted words. But remember, no narrative, just images.

Daily ledes

This drill is perfect for pre-bedtime journaling.

- Choose three events/moments from your day.

- Jot down the 5Ws: when, where, who, what and why.

- Write a lede (the first sentence or paragraph of a news article) that contains all 5Ws.

Example:

- You went to the dentist and got your teeth cleaned.

- When: 11:30AM, where: dentist office (43 Main Street), who: hygienist David, what: tooth cleaning, why: six months since last appointment

- Lede: At 11:30 this morning, dental hygienist David Smith faced off with a six-month old plaque formation on Patient X’s right rear molar, a struggle that resounded through the office at 43 Main Street.

Bonus game! #semanticfieldgoals

Yes, I just wanted to write #semanticfieldgoals.

It’s also a good game.

A semantic field is a set of words related by meaning, for example colors, plants, foods, senses, etc. For the sake of this drill, any category will do.

Choose a category

- List all the words you can think of related to that category.

- Choose one of those words as the starter for a new list.

- Repeat as often as you like.

Let’s try chemistry:

- Chemistry: periodic table, ion, Madam Curie, Nobel Prize, beaker, lab, Bunsen burner, ion, orbital, atom, atomic weight, electron, proton, neutron, bond, reaction, element, carbon, organic

- Atom: ancient Greece, Democritus, particle, bomb, Oppenheimer,

- Ancient Greece: philosophy, alphabet, city-states, wine, Homer, Sparta, etc.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Play a round or two of one of the games and post your results in the comments!