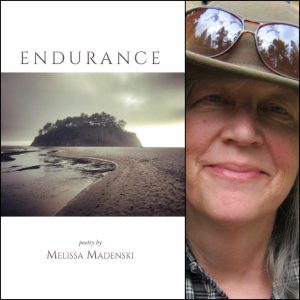

Welcome to ‘Between the Lines’ – interviews with teachers, writers and writing teachers on specific aspects of their craft. This interview will be split into two posts to do justice to Madenski’s generous sharing of time and wisdom. Part 1 covers her biography and writer’s origin story. Part 2 will focus on craft and teaching.

Full disclosure: Melissa and I have known of each other since I was growing up in Lincoln City, Oregon; her children attended my mother’s day care. About a decade ago, I reached out and shared some of my writing. She responded with characteristic generosity and has become a dear friend, mentor, exemplar.

“I’ve had everything in my life I wanted, but not one thing went according to plan.”

Melissa Madenski delivers this statement with poise that belies the extraordinariness of the claim.

White hair frames dark tortoiseshell glasses and silver hoop earrings. A boho-chic bob to make Anna Wintour green. The kindled joy in her eyes refracts through the the kitchen-dining-living space of her Portland, Oregon home, which is as spare, chic and elegant as she: drip coffee-maker, glass-fronted book shelves, black-and-white prints on crisp white walls.

Elsewhere, these might be bland markers of commodified good taste. But they are Madenski’s tools: functional and essential as carpenter’s adze or blacksmith’s tongs.

Born and raised in Portland, Madenski moved to the Oregon coast as a young woman, taught school, married, had children. One imagines a life rich in the delights of partnership and parenthood: time-poor, perhaps, but abundant in laughter. A time to make one say, “I’ve had everything I wanted.”

But: “Not one thing went according to plan.” The rosy narrative ended in a thunderclap moment when Melissa’s husband, Mark, died, aged 34. Their children, Hallie and Dylan, were one and six years old; their hand-built wooden house in the Siuslaw Forest unfinished.

“My healthy, athletic husband had simply stopped breathing,” she wrote in her 2015 essay, ‘Starting Over.‘ “We would soon learn that an arrhythmia shook his heart until it stopped.”

Such an unthinkable, unspeakable loss can drive unbelievers to their knees and turn Christian soldiers into atheists. How many people, in that crucible, muster the grace to craft an original response?

Madenski mustered — no — created that grace.

“That’s when I started to write every morning,” she recalls. “I missed Mark very, very much; I held onto writing for my sanity. I’m not an early riser, but I’d set my alarm for 4:30. It was a wood-heated house, so, freezing. I’d stick my head under well water – also freezing – make a latte, then shut myself in my office.”

Deep roots

Though Madenski traces her deliberate writing practice to the cataclysm of loss, its roots reach across generations and oceans.

The youngest daughter of a traveling salesman and a homemaker, Madenski grew up in Portland, happy to daydream alone beneath a spruce tree in their yard. Her grandmother, an immigrant from Norway, lived with them. “I credit her with raising me. She told me lots of stories.”

They were the stories of a vibrant and spirited woman who “hiked, rode horses, lived in logging camps.” A woman who knew, too, what it was to be struck by fate.

A burst appendix led to an infection that ruined her grandmother’s hip. In an era before accessible replacement surgery, this irredeemably altered the last 30 years of her life.

“She lost everything that she loved.” Madenski sits with her memories for a moment, then continues. “My grandmother been a seamstress, so my mother would bring her thread and fabric. She sowed until the last three days of her life. It was like writing: the one thing no one can take away.”

Another thing no one can take away: the example of a woman who chose not to be defined by suffering, but to — Penelope-like — stich and unpick, stitch and unpick, until the stitching and the unpicking became a new tale.

Rattle’s Ekphrastic Challenge

Meandering path

Though “drawn to stories,” Madenski didn’t want to be a writer. “As a kid, I only wanted to imagine. I would go to bed early, lay there and create stories where I was always the heroine.”

Madenski was a voracious reader. But it wasn’t until high school that writing began to glow as an idea.

“I had a magnificent teacher, Ruth Strong. She was a botanist as well, who after she retired wrote Seeking Western Waters – the Lewis and Clark Trail from the Rockies to the Pacific.

She was the first person who said I was a writer; the first person to believe in me as a writer. There was no big lineage: I kept a boring diary, which thankfully was lost in a house fire, but what I’ve come to believe is that so much of writing is story. We are wired for narrative. We’re wired for beginning middle and end.”

Despite the brush with inspiration, Madenski began “a traditional path”, earning a degree in elementary and special education from Portland State University.

Her first job, age 22, was teaching second grade in a public elementary school. “It was hell,” she says. Disadvantaged students. A teachers’ strike. The inevitable tribulations of being green and unschooled. “It was trial by fire. I witnessed things I’d never seen. I had to learn to report abuse. Teaching wasn’t teaching, it was trying to keep people’s head above water.”

The steeliness of her working-class Scandinavian ancestry flashed when she refused to sign a contract for the following year until the principal promised things would change.

After fulfilling her childhood dream of moving to the beach, Madenski taught at Oceanlake Elementary in Lincoln City and at a private school in Neskowin. Although she calls the freedom and miniscule class sizes of independent schools “heaven,” she is quick to say, “I believe in public schools.” Only there did she find the diversity that stretches and challenges.

Beginning (Again)

Mark’s death precipitated her out of conventional classrooms. “There are single women who could raise kids and teach, but I couldn’t. I had some insurance money and the house, and thought, I’m going to piece things together.”

Her next first job was driving to Hebo Ranger Station to teach English to migrants employed in the local dairy industry. “It was a good time to not be alone. I was in grief, but so were they,” she muses. “Dairy milking is a hard job, they were sending money home to Mexico, but they had the most wonderful stories.”

Teaching English became one of the legs of the “three-legged stool” required to stay afloat in the Oregon Coast’s parlous tourist economy.

It was then, too, Madenski began the cold-water morning writing practice that she maintains to this day (“I wake up at 5AM, come to the table and write. It’s home to me. It’s stability”).

Her most lucrative year as a writer brought in $6,000. (“It wasn’t enough, but it was a leg.”)

Other legs included teaching at the NW Writing Institute at Lewis & Clark College, founded by friend and fellow author Kim Stafford; running adult literacy programs in libraries; leading writing programs for children; teaching citizenship classes to immigrants; mentoring young authors; and creating her own writing workshops.

“These jobs I pieced together didn’t give me a big retirement or benefits,” she says, matter-of-fact, “but they gave me a lot of experience.”

To anyone who says, experience don’t pay the bills, Madenski’s life is an emphatic beg to differ.

Experience can make the difference between between resilience and collapse.

A couple of years ago, Madenski had hip surgery, then broke her femur in a fall. Cue months of pain, compromised mobility, physical therapy; Covid and long Covid. A downward-rushing torrent that could sweep a person away.

“I was trying to keep going as before, and I kept falling. So I learned to say ‘no’ so I could say ‘yes’… yes to friends, family, writing. I don’t expect to grow old without pain; it doesn’t shock me or surprise me.”

The simple lucidity of the statement is a gong.

It doesn’t surprise me.

The voice of experience.

“I am at peace,” Madenski adds, stating what shines in every plane of her face and every gesture. “That’s a skill for life: not to take things personally that are not. Life teaches you what is personal. Death is not. It happens to everybody. The world is completely sorrow woven with happiness. I’ve learned not to forget that all day long.”

Connect

Web:

- Her Photos, My Poems (a collaboration with daughter Hallie Madenski)

Books:

- Field Notes (with Hallie Madenski)

- Endurance

Look out for Part 2 of the interview, where Melissa shares her insights on teaching writing.

The Handmaid’s Tale came courtesy of the library. I don’t get Atwood aesthetically in the same way I don’t get, say, Thomas Wolfe or D.H. Lawrence. Her politics are admirable though. Astute women are

The Handmaid’s Tale came courtesy of the library. I don’t get Atwood aesthetically in the same way I don’t get, say, Thomas Wolfe or D.H. Lawrence. Her politics are admirable though. Astute women are  To my delight, Susan Cooper didn’t make the same mistake in The Dark is Rising. Full confession, I’d never heard of it till reading a

To my delight, Susan Cooper didn’t make the same mistake in The Dark is Rising. Full confession, I’d never heard of it till reading a